Words: Em Dabiri Photography: James Fisher

He emerged through the dreary light, from the undergrowth, swatting a branch out of his path. “Hi” “Hi” “How are you, where are you from”? The dreaded question! Although here in the Jungle it assumed a new texture; no longer the cloaked demand to justify the incongruous presence of your brown body -in whichever pastoral scene history has perversely seen fit to locate you- but rather as a request for more information, between two people who belong and don’t belong in different ways.

I don’t belong in Calais. Put bluntly, what am I doing here: Where are you from? Does he belong in Calais? Does anybody? How has he ended up here? Which horror, what brutal regime has he fled? Which of the desperate routes has he taken to find himself here, where nobody belongs, where people simply exist (or not), waiting for a chance to live: Where are you from?

You just click with some people don’t you? The conversation between us was easy, unselfconscious, despite the slight but persistent tremor possessed by my new friend. The shaking I attributed to a deep, toothed scar that traversed his head, a legacy of the journey no doubt, perhaps some sort of nerve damage he’d sustained. In many ways we had a lot in common: both former university students, he in law, myself in sociology, both committed to social justice, his aim is to make it to the UK to complete his disrupted studies, graduate, and practice law to protect vulnerable people.

“Are you hungry? Would you like to have lunch with us?” During the three days I spent in the Jungle, I was struck by the unerring hospitality of my Ethiopian, Eritrean and Sudanese hosts. I downed countless cups of sweet hot black coffee, and was treated to numerous meals, creatively assembled from whatever was available. A far cry from the fragrant food prepared in the lands of their birth, but the attention to detail, and the communal nature of each meal, nevertheless demonstrated the centrality of food, community and conviviality in these African cultures.

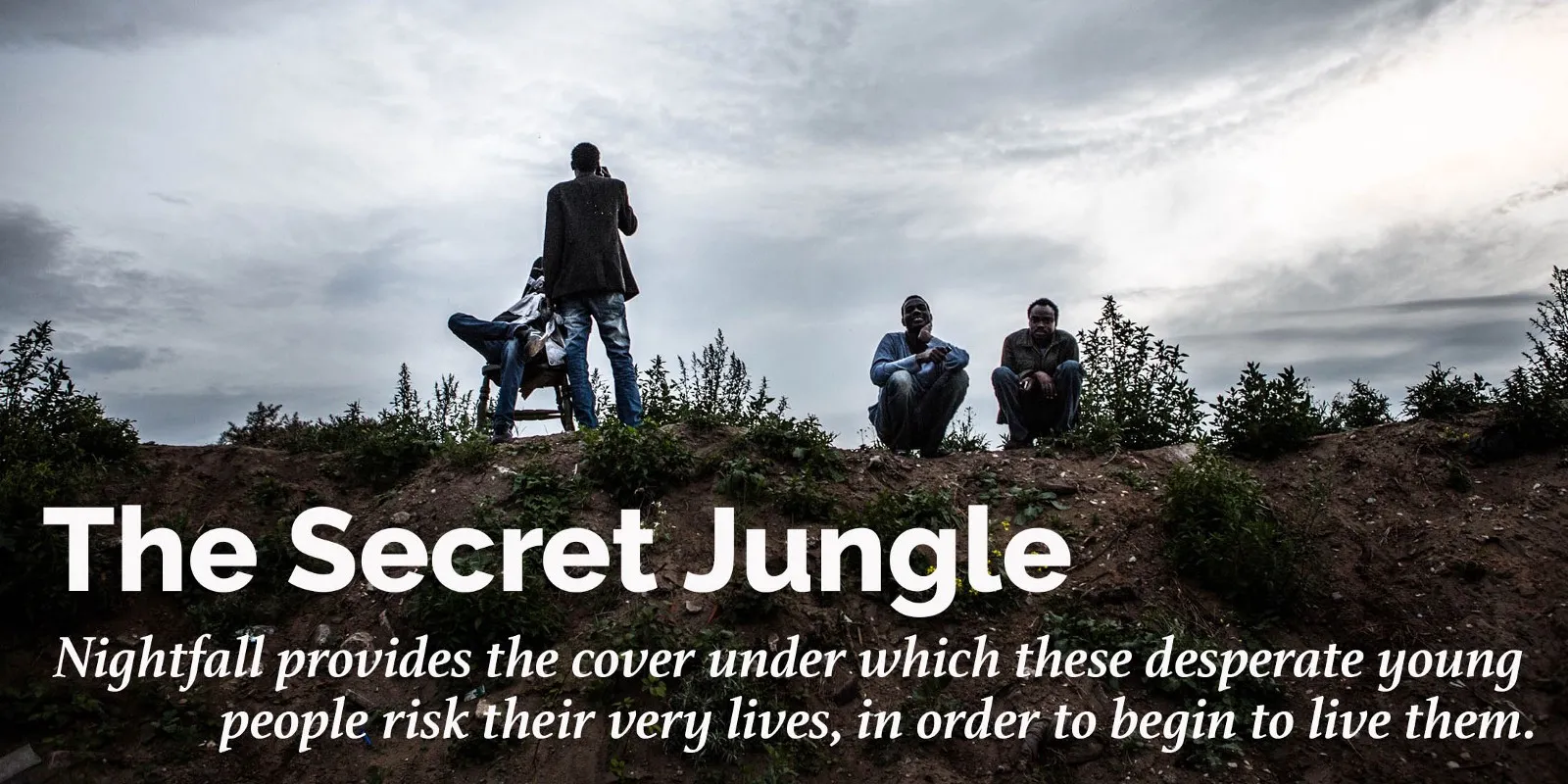

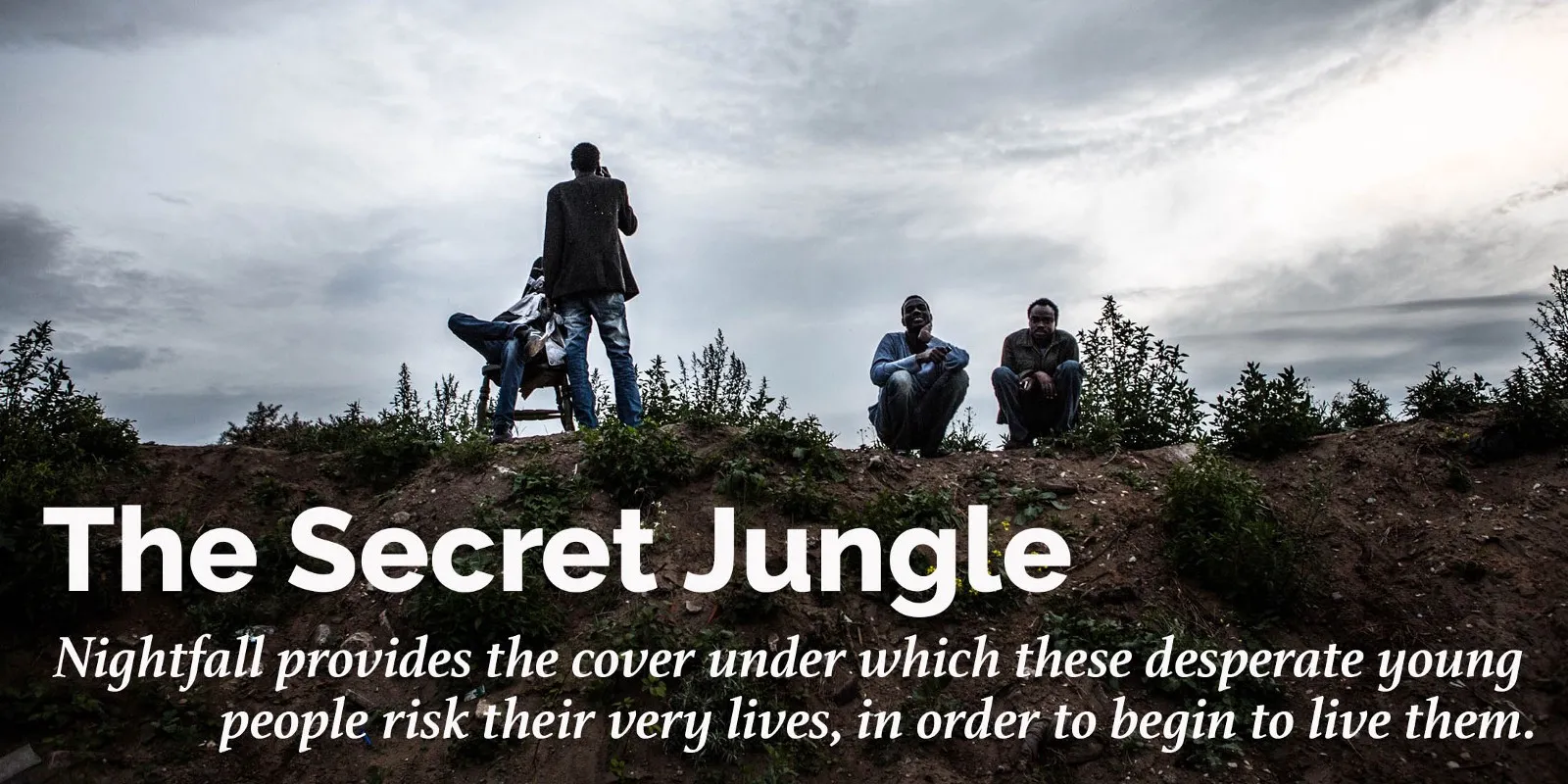

Removing my shoes in the doorway as was the custom, I entered the tent, home to approximately 30 men of varying ages but most, probably in their 20s, perhaps their 30s. A flurry of activity ensured a clean, dry blanket was procured for me to sit on. My arrival was something of a departure from routine; there were no other women in this particular camp. The Jungle is a liminal space, as restless as its inhabitants, comprised of a former landfill site, but also constituting various unfixed satellite camps whose locations morph and shift. It was in one of these smaller, ‘secret’ jungles that I now found myself. The men had sent up camp here because it was closer to the entry points where night after night they attempted to break into the vehicles that they pray will transport them to perceived safety. Most of the men were keen to talk, to make sure I had enough to eat, enough to drink, to ensure I was comfortable, to take pictures with me. I think my presence was perhaps unusual too for the fact that most, if not all of the other visitors to the camp are white.

Where are you from? On my first day I had been answering Ireland, to little reaction, but after a couple of hours, I started to reply Nigeria, which changed everything. “Ah you are our sister”. Where are you from? “You look Habesha” “You look like Sudanese”. My own sense of belonging is so fractured, that anybody claiming me remains not only a novelty, but more than that, a balm, bestowing an ease I don’t often get to experience. The fact that I felt something approaching a sense of belonging in an unofficial refugee camp on the edge of France, when such a sensation alludes me at ‘home’ in Ireland, the country of my birth, says a lot about identity and belonging for black Europeans, a different but related story.

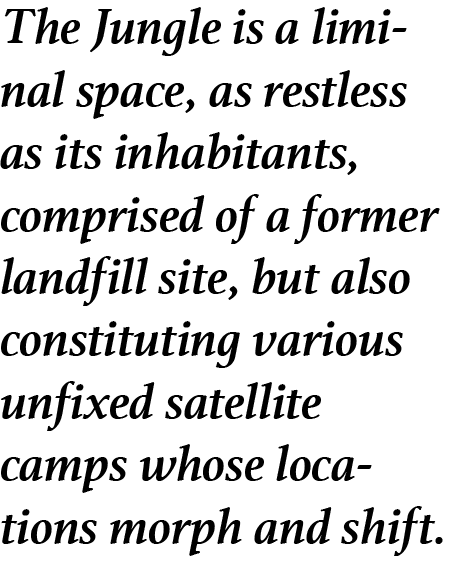

Despite having reached Europe, many I spoke to simply did not feel at home in France, in large part because they do not speak the language. English on the other hand most speak fluently. For those in Calais, Britain, The United Kingdom exerts the strong pull of the homeland, a motherland, a place of protection and sanctuary. The colonial myth of Britannia still permeates the far reaches of the globe. The English publics’ ignorance of their country’s colonial legacy astounds me, but then again I am not from the metropolis, not English, not British even. I am a daughter of the periphery. Irish-Nigerian, born to parents that speak English (of course), from countries whose national language is English (of course). English is the parameter of my thoughts, of my imagination, and my soul. British foreign policy crushed the Gaelic language, ground it down into abjection, until it was little more than a burden forced upon you at school, rather than the repository of your own distinctly non Anglicized civilization. My father’s language Yoruba, reconstituted by the British as the epitome of barbarism, jibberish, became evidence of African’s primitive savagery. To get ahead, to succeed, to survive, the educated, the successful, had to speak English. Through the enforcement of English, they got inside our heads, took away our prayers and gave us curses, replaced our gods with devils. For everything we had which they did not understand, they took our names and in their place gave us English words that forever warped and twisted their meanings. Our thoughts, no longer our own were re-made in our “superiors” image, so that nothing, not even that vast internal landscape of the soul was ever really ours again. And maybe it’s because of Britain’s own behaviour abroad that the nation remains so pathologically afraid of immigration. But know this, not everyone is like you.

Most indigenous African cultures are not imperialist. Adoption and adaption, of other cultures, rather than destruction and domination, remains the name of the game. In-fact the examples in which you find the contrary are most prevalent in religious conversion, namely Christianity, and guess who introduced that particular delight? Conquering and colonizing has consequences, the reverberations of which don’t just disappear because their reality is no longer profitable. Britain sold the world the myth of its “greatness”, and there are those who do not yet realize the fallacy. And so they come to the UK, and they will continue to come. That is your legacy. We come here because you went there!! Many won’t see the rot that constitutes the foundations of the edifice until after they make it to these shores, unless of course they die in the attempt, which many will. However, should they reach Britannia and gain access to this grey little isle, they will see for themselves that there is no wizard, only a wee little man, projecting an image garbed in the shreds of a prestige which can only be maintained through distance. Get too close and the mirage disappears.

People in the camp clung to the myth of Britain’s ‘greatness’ with a conviction I found chilling. Most had already spent over a year travelling to reach the Jungle, undertaking a harrowing journey, spanning national borders, deserts, and oceans, loved ones left behind. I asked my new friend how he’d found the crossing. He told me he was one of the lucky ones, departing from Egypt rather than Libya, where conditions are generally more favorable, but where the price of the boat is double. “How long where you at sea?” I inquired. “16 days. It was only supposed to take 5 but the crew lost the compass and we were lost at sea”. “What about food and water?” “Well we had enough for one week, so after about 10 days many of us thought we would die. In the end only a few did, and here I am.”

“Wouldn’t you just stay here in France, after all that”? I ask. “No England, England, we must make it to England. Every night we try. At least 9 of us have died trying in the last month, a friend lost an eye, another broke his back, but not me, I will make it.”

Inside the tent my new friend tells me about his university studies. He was three years into a law degree with one year to complete… his voice begins to waver. He shows me a picture of a pretty young woman with long hair and black kohl eyes. “My wife, I haven’t seen her in a long time” he murmurs staring off into the distance.

Lunch is served and about 20 of us eat spicy pasta from a communal bowl. After everything has been cleared away, my new friend inquires if I play cards. I do, in-fact I love cards. “Watch this”, he instructs me with a mischievous look.

A complex performance unfolds, in which my host predicts the numbers that will turn up next in the pack. “What the hell”? I know it’s a trick but I can’t for the life of me work out how it’s done. “Ill show you”, he offers. Over the course of the next hour he painstakingly attempts to teach me, but I’m just not getting it, much to the amusement of the small audience that has formed. Eventually after careful tutoring I crack it, and perform the trick successfully, if not somewhat uncertainly, on my own.

Darkness begins to gather and I know I must leave. Like I said I don’t belong here. At nighttime, the charged, suspended state of stasis is replaced by hurried activity. Nightfall provides the cover under which these desperate young people risk their very lives, in order to begin to live them. I give my friend my number. I leave. He never calls. I never see him again.